SF State researchers return to Burning Man for a new look at the festival’s environmental impact

The team, from the University’s School of the Environment, wants to know if sustainability efforts are making a difference

Ten years ago, Clarissa Maciel learned that her professor would be absent from class because he was at Burning Man. As a San Francisco State University Geography undergraduate, she found the news both cool and perplexing. A college professor at a week-long festival famous for raucous music, elaborate art installations and anything goes attitudes? It turned out that her professor, now School of the Environment Co-Director Andrew Oliphant, was there to work on a research project with a master’s student: an analysis of the micrometeorology of a transient city in the desert.

All this became a faded memory for Maciel — now a San Francisco State graduate student — until she found herself heading to Burning Man to help Oliphant and other researchers conduct a follow-up to the 2013 study. In addition to gathering more data, the team (which was made up of researchers from SF State, San Jose State and UC Berkeley) wanted to understand if and how Burning Man’s new commitment to sustainability is making a difference on the event’s carbon footprint. Just like in the past, team members measured carbon emissions before, during and after the construction of the temporary city on the playa (flat and dry land) in Black Rock City, Nevada.

Burning Man organizers have launched efforts to become carbon negative and participate in programs to offset the festival’s carbon emissions. Oliphant and his team want to know if this is making an impact.

Maciel is particularly interested in how humans can work with their landscape to tackle the effects of climate change. For her master’s thesis, she’s studying soil greenhouse gas emissions and the impact of farm management practices on reducing emissions produced by agriculture. Her interests and skills nicely complement the work happening in Oliphant’s study.

“Everybody’s focused on planting more trees. Yes, that is great, but I want us to focus on the actual land that’s underneath us and focus on the soil and nurture the actual soil,” Maciel said. “That can help us improve the emissions that are released into the atmosphere.”

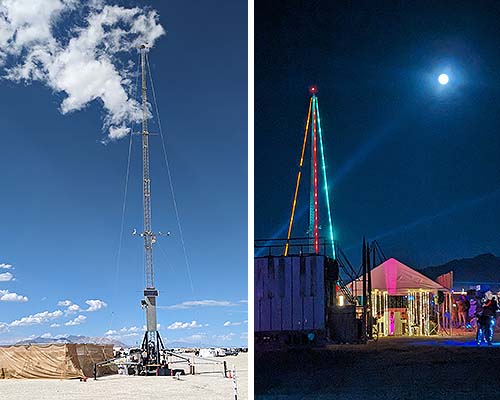

At Burning Man, the researchers set up a 100-foot flux tower that measured CO2 emissions, wind speed and turbulence, air and playa temperature, and more. The tower was positioned close to the center of the city near a lot of foot traffic. Since she’s interested in studying the emissions that come from the land, Maciel used a chamber — a literal cube that collects gasses emitted from the soil, that’s similar to what she uses for her thesis work — to measure emissions coming from the bare playa at a location that was relatively pristine and at a second site with more foot traffic. It means she can start studying the emissions coming from the land and how more than 70,000 attendees might be affecting it.

With hot days, freezing nights, strong winds and occasional torrential downpours, the weather during Burning Man mirrors the unpredictability that the rest of the world is starting to experience more and more. As Maciel sees it, that makes the festival even more valuable as a microcosm of larger climate forces.

“I think that we should always be prepared for crazy weather, especially in our current time,” Maciel said, pointing to the unexpected hurricane in Southern California last month as an example. “That’s exactly why we’re doing these studies. Climate change? We’re in climate chaos. We never know what to expect.”

The team is still analyzing the latest data, but in 2013 they saw that the transient city’s CO2 emissions were comparable to Mexico City and parts of London. Maciel is interested to see if there’s a shift in emission trends, especially after climate change literally rained on the experiment. The rain might have impacted the playa microbial biome and thus CO2 emissions from the surface, she explains. She thinks the study could have applications beyond the annual festival.

“Burning Man could be a model for a carless city. There are very few cars there. Most people are walking or using a bike. If the emissions are equivalent to that of other urban cities, we could look at [Burning Man’s] transportation sector and compare it to those cities,” she explained.

The 100-foot flux tower during the day (left) and night (right).

Photo credit: Andrew Oliphant and Clarissa Maciel

Clarissa Maciel taking measurements using her chamber. Photo credit: Andrew Oliphant

Although Oliphant was already intrigued by the microclimate of Burning Man’s ephemeral city, it was his former student Garrett Bradford (M.S., ’15) who helped officially kick off the project in 2013. Bradford frequented Burning Man and wanted to study the role of buildings on turbulence and airflow there for his thesis. This year, Bradford, along with his 4-year-old son, traveled to Burning Man to lead the climate science themed camp. School of Environment Lecturer Malori Redman also returned this year after participating as an undergraduate researcher 10 years ago. This year, she rode a bicycle outfitted with equipment to measure the city’s impact on temperature, humidity and CO2 concentration.

Key to the success of the original Burning Man experiment and this year’s follow up was the faculty expertise and the interests and skills of students like Maciel, Bradford and Redman. For Oliphant, these types of partnerships have been some of his most rewarding research collaborations and have taken projects in directions he never envisioned.

“My advice to students is to understand and appreciate the unique value that they can bring to any research project and to reach out to professors regarding research opportunities,” Oliphant said. “When given an opportunity, fully engage as a research partner especially sharing ideas and questioning assumptions.”

Learn more about research happening in the School of the Environment.

Tags