Ranked-choice voting linked to lower voter turnout

Jason McDaniel, associate professor of political science, has conducted a number of studies examining the impact of ranked-choice voting on voter turnout and believes voting should be made easier.

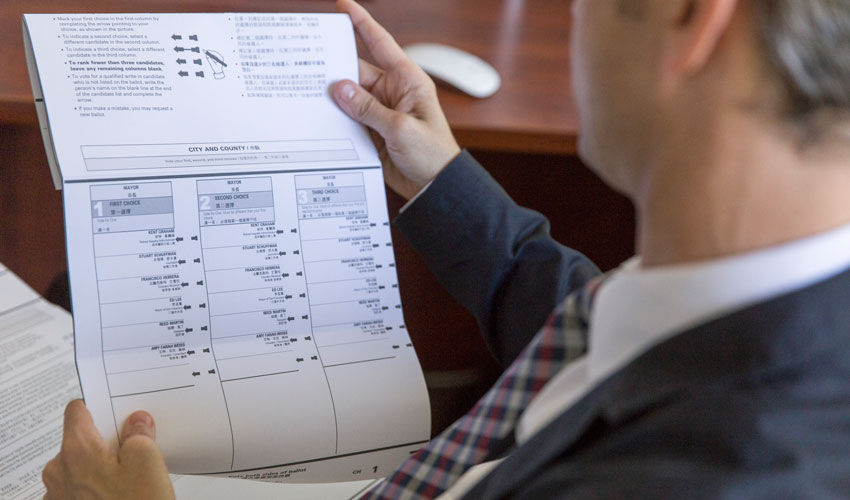

On Tuesday, Nov. 3, San Francisco voters will return to the polls and cast their votes using the ranked-choice voting (RCV) system, a relatively new method that allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference, thus eliminating the need for a runoff. But as Election Day draws near, a recent study reveals that RCV may actually make voting more difficult.

The research from San Francisco State University Assistant Professor of Political Science Jason McDaniel, recently published in Journal of Urban Affairs, analyzed racial group voter turnout rates in five San Francisco mayoral elections from 1995 to 2011. The 2007 and 2011 elections used RCV ballots; the 1995-2003 elections used the traditional two-round, primary runoff system.

The analysis revealed a significant relationship between RCV and decreased turnout among black and white voters, younger voters and voters who lacked a high school education. RCV did not have a significant impact on more experienced voters, who had the highest levels of education and interest in the political process.

The more complicated ballots required by the RCV process might have caused voter confusion and ballot error, McDaniel said. In addition, the process of candidate evaluation required to rank-order multiple candidates is also more difficult for some voters to understand and may be more challenging than choosing one preferred candidate. These "information costs" associated with RCV ballots make voting accurately difficult for some. For example, cues that voters typically look for, such as party affiliation, are no longer printed on ballots as a result of electoral

reform initiatives.

Jason McDaniel, associate professor of political science, says voting in local elections can be a difficult and confusing process for many people.

Previous studies have shown that ranked-choice ballots tend to increase incorrectly marked ballots (called overvotes) but decrease incompletely marked ballots (called undervotes). Studies have also found high rates of disqualified ballots due to voter errors. In addition, some minority groups were particularly disadvantaged by the RCV process, with correlations between overvotes and both foreign-born voters and those with a primary language other than English.

"Voting in local elections can be a difficult and confusing process for many people. RCV increases the complexity of voting, which raises a barrier to participation for those who are least likely to participate and have their voices heard," said McDaniel.

Further research is needed to determine how RCV affects racial group voting preferences and whether it has the potential to affect election outcomes, he added.

According to McDaniel, RCV is an example of a recent electoral reform with roots in the Progressive Reform Era around the turn of the 20th century. Reformers advocated for nonpartisan elections for local office and off-year election timing, which has led to significant decreases in political participation and voter turnout, he notes.

"The result of over a century of reform efforts has been the creation of a system of urban elections that is riddled with participatory inequalities and which consistently works to the benefits of some groups compared to others," McDaniel said.

Though its popularity has increased since the controversial Bush-Gore U.S. presidential election in 2000, fewer than 20 cities nationally have adopted the system. San Francisco voters passed an amendment in 2002 to use RCV to elect local officials by majority vote, with its first RCV election held in 2004.

McDaniel's research into RCV continues. Today, more than six years after beginning his initial research into the impact of RCV, McDaniel says, "The one thing I keep coming back to is that voting should be made simpler. More people voting is a good thing. Period."