First TV documentary on homosexuality made public

A man in horn-rimmed glasses and a bowtie appears on screen, a grave expression clouding his face. He introduces himself as James Day, the general manager of KQED, and, still unsmiling, continues. "The program you are about to see deals with a subject that is controversial, delicate and, to some," he says, "downright unpleasant."

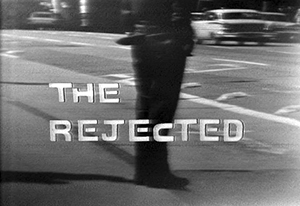

"The Rejected," the first American television documentary to explore homosexuality, was once considered lost. The program has now been made available by the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive at SF State.

The subject is homosexuality. In 1961, this documentary, "The Rejected," became the first to address the topic on American televisions. Widely believed for decades to be lost, "The Rejected" has been rediscovered and made public by the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive at San Francisco State University.

The hour-long documentary, which repeatedly refers to homosexuality as a "problem" of major proportions, offers insight into the prevailing opinions of Americans half a century ago, with doctors, legal critics, religious figures and gay men themselves weighing in.

In the program, former president of the American Psychiatric Association Karl Bowman asserts that homosexuality is a "deviation" that can be "cured," adding, "Treatment is difficult. … Much will depend on the individual's attitude and his wishes to be changed."

The suggestion that a cure be sought for homosexuality emerges repeatedly, including from Rabbi Alvin Fine, who condemns homosexuality from a spiritual perspective. "The person in this situation is like anyone else with an illness and should be cared for as such, with love and compassion," Fine explains.

Such outdated notions, said SF State's resident film archivist Alex Cherian, contribute to the documentary's historic value. "'The Rejected' is important because it's the first time on television that this subject was addressed. As crazy as some of it may seem, it's worth watching from that perspective," he said. "If you look at all the material we have in our archive, you can actually chart through the decades how things have changed from 1961 to 2015."

Around 2009, Cherian said, he started receiving calls from professors across the country wondering whether the archive, which holds extensive KQED footage, had "The Rejected" in its collection. At the time, Cherian had never heard of the documentary, but he consulted directly with Irving Saraf, one of its co-producers, who lamented that the footage was long lost.

Cherian, collaborating over several years with KQED archivist Robert Chehoski, checked with other college libraries and archives before learning that the Library of Congress had preserved the documentary in its original format of 2-inch quad videotape. From there, Cherian reached an agreement with KQED and WNET, which held rights to the footage, to finally make "The Rejected" available through SF State's Digital Video Information Archive (DIVA) at the end of May.

"We already have a well-recognized online archive that streams KQED material from that period," Cherian said. "So it makes sense for us to have it as part of that collection."

The medium of television, so influential in the 1960s, provides a unique cultural perspective into the society of the time a program was made, Cherian said.

"A television sits in the corner of your living room and brings information into your home," he said. "If a program like this is on your TV and you're watching it, or at least not turning it off, you'll be considering the issues it raises. Over time -- and you might not know it -- it may be changing the way you think."

At one point in the documentary, gay rights activist Harold Call memorably seizes the opportunity to make an impact. Adopting a defiant tone, his voice slightly raised, Call issues a plea for understanding and acceptance.

"The homosexual is no different than anyone else, except perhaps in his choice of a love object," Call declares. "He desires the same kind of rights to live his life freely and without interference, to pursue his happiness as a responsible citizen."

With "The Rejected" now available online, viewers can glimpse history: In that moment, more than 50 years ago, the face of the so-called "rejected" flickered on thousands of black-and-white television screens, seen by many Americans for the first time.

-- Beth Tagawa