Study examines when teachers go off-script as a teaching tool

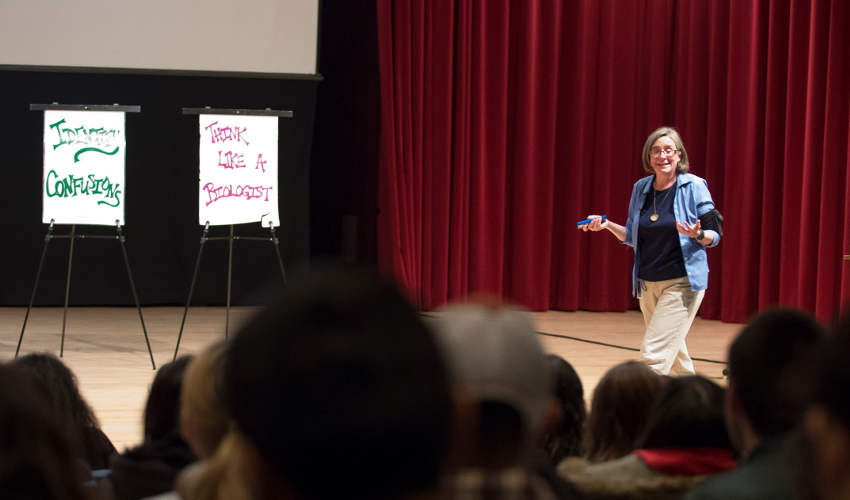

San Francisco State University Professor of Biology Kimberly Tanner in the classroom

37 SF State Biology faculty, staff and students collaborate on education research

Think about a teacher you had whose teaching style or personality made their lessons more interesting and more accessible. What if it was possible to measure that rapport? A new study, led by San Francisco State University Professor of Biology Kimberly Tanner and featuring 37 SF State faculty members, students and staff as coauthors, shows that it is possible — and suggests that this factor may be crucial to the learning process.

While an instructor’s first impulse may be to maximize limited class time by sticking strictly to the material, that approach has its downsides, according to Tanner. “Then we’re not coaching our students, and we’re not cheering them on,” she said. “We’re not trying to guide them as a knowledgeable expert.” Teaching isn’t just about providing information, Tanner argues. The challenges of keeping students engaged with course material can come down to how that information is framed, especially for students who are underrepresented in higher education.

Tanner and other Department of Biology faculty began studying these interactions during a three-year professional development effort to improve teaching in the department. The first step was to develop a system that could reliably identify and describe the things instructors say that aren’t related to course material, which the research team call “instructor talk.” After recording and analyzing a classroom’s instructor talk during one semester, the team created a rubric with categories like encouraging students to collaborate, building relationships through personal anecdotes and giving study tips.

After that trial run, researchers expanded the study to more than 60 courses in community colleges and at SF State and developed a simpler, less time-intensive way to study instructor talk in classrooms. That expanded analysis revealed that every professor in the study used instructor talk in their lectures, and in many courses, it was recorded in every single class session. The team published their results in the journal CBE — Life Sciences Education on Aug. 30.

The team found that 90% of instructor talk could be described by the categories they first developed, proving that the system worked. “You can really say this is robust across a lot of different types of courses,” Tanner said.

Ten percent of the recorded instances of instructor talk, however, fell into a category that had been overlooked in the first analysis, which the researchers call “negatively phrased instructor talk” — statements that may discourage, distract or alienate students. Tanner remembers an example from her own education. A professor told her class, “We’re not going to be studying your dad’s genetics,” she recalled. “And I spent the next 15 minutes thinking, ‘My dad never studied genetics. I’m the first in my family to go to college. Do I really belong here?’”

That, Tanner says, exemplifies the kind of long-lasting impact instructor talk can have on students. Years later, many students won’t remember the details of their class lectures. But they’ll remember an anecdote that encouraged them to pursue their field or a professor’s discouraging comments that made them drop a course. And those experiences may have an especially profound impact on students with marginalized identities — students of color, LGBTQ students, first-generation college students or women in STEM fields — who might already be subject to negative stereotypes about their ability or may feel isolated from the academic community.

The researchers say this study will open the door for future research into how the phenomenon of instructor talk influences students’ academic experiences and decisions. Armed with this knowledge, professors can learn how to build a better classroom culture.

What Tanner hopes teachers will take away from this study is how important it is for instructors to reflect on their lectures and consider how they sound from a student’s perspective. “The students listen to us all the time,” Tanner explained. “Maybe we need to purposefully listen to ourselves.”