Student’s project aims to speed up the hunt for aliens

The SF State Observatory

Database will ensure that E.T.-seeking scientists don’t search the same patch of sky twice

Are we alone in the universe?

It’s a question some scientists have dedicated their lives to. But according to San Francisco State University Physics and Astronomy junior Andrew Garcia, even several lifetimes might not be enough.

“If we want a meaningful answer to that question, it’s going to take multiple generations to complete,” Garcia said. That, he explains, leads to another question.

“How do we get astronomers three and four generations from now to see where we’ve looked and how we’ve looked,” Garcia said, “so they’re not wasting their time looking under the same rock?”

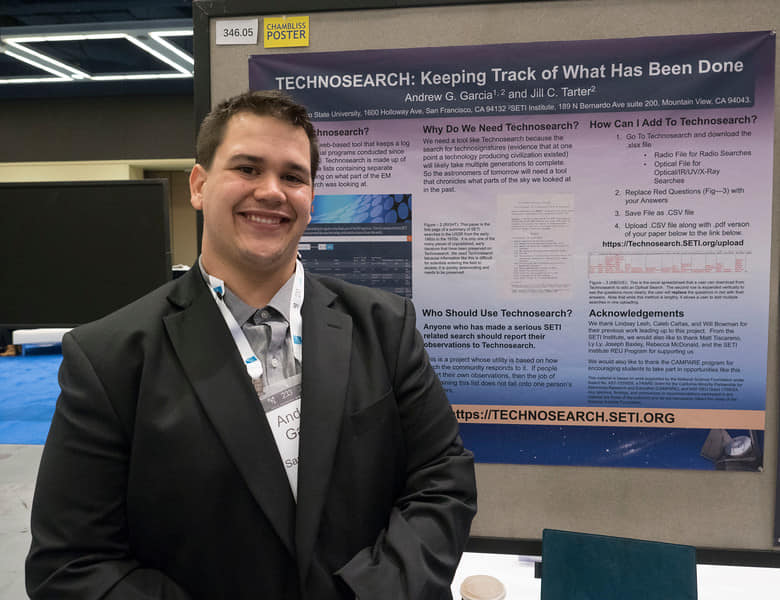

Student Andrew Garcia poses with his poster at an American Astronomical Society meeting.

Garcia spent last summer addressing just that question in a project with the SETI Institute, the world’s foremost alien-hunting organization. (SETI stands for the Search for Extraterrestrial Life.) The solution that Garcia helped engineer is a web-based tool called Technosearch that collects and organizes studies in which scientists searched the stars for traces of alien technology. Future astronomers can then check the website before conducting their own searches. Garcia presented the work earlier this month at the 233rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

“Technosearch is a record of where we’ve looked in an easy-to-see list,” Garcia explained. Each entry on the site lists a published study, including information on where in the sky those scientists looked, when they looked and also, crucially, how they looked. If you simply search a patch of space for visible light, for instance, you might miss an alien radio broadcast, or maybe a pulse of infrared heat from a Dyson Sphere (a theorized structure that could harvest most or all of the energy of a single star).

The database is necessary because the results of many studies conducted by scientists — pointing their instruments at the stars to look for traces of intelligent life — are inaccessible in one way or another, stuck behind digital paywalls or in the physical pages of journals. So far, close to 150 of those studies populate Technosearch, and Garcia has high hopes that number will keep climbing as fellow researchers and enthusiasts catch on and start to submit studies from their own collections.

Garcia found his summer position through the CAMPARE program, and his work was funded through the National Science Foundation. He went into the program with a focus on astronomy and little experience in coding. But just a few weeks in, he was building a website and populating it with studies collected over the decades by his mentor Jill Tarter, chair emeritus and former director of the SETI Institute.

As a student whose academic interests range from geology to math to English, Garcia says working in such a multidisciplinary group was energizing. “They have 23 separate disciplines among the scientists in the institute. People with a lot of different ideas coming together to tackle a very big question, that was something that kind of enthralled me,” he said.

And Garcia has stayed involved, too: He’s continued working on Technosearch as an independent study throughout the semester. “For the most part the project is almost out of my hands,” he said. “But I want to remain on as a moderator.”

So far, the vast majority of anomalies scientists have spotted in the skies are better explained by natural phenomena than by aliens. And it may be that extraterrestrial life — if it’s out there — will never show itself to us. But thanks to Garcia’s work, it’s now just a little bit easier for astronomers to make sure that no stone remains unturned.