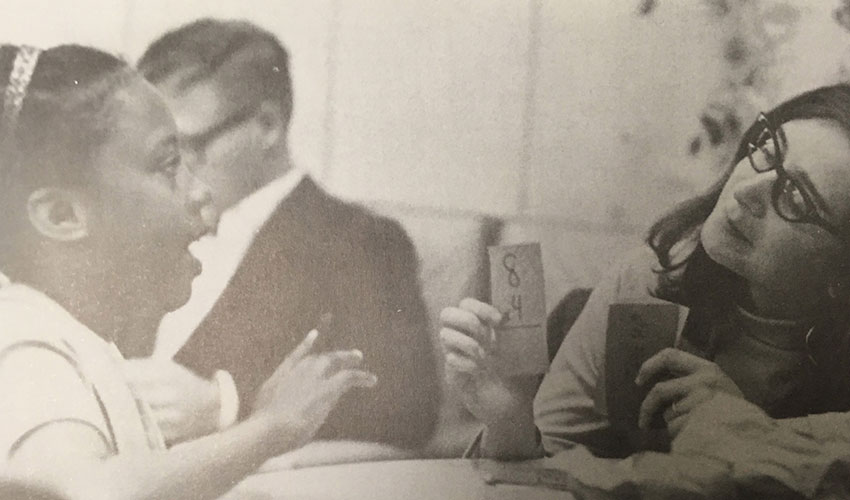

At SF State, community service was another form of campus activism

An SF State student helps a child with her studies. Several hundred SF State students volunteered in tutorial programs in low-income neighborhoods in the city in the 1960s.

Students tutored at-risk kids, offered advice on military draft and formed service learning programs

The last of six stories about the lasting legacy of the Summer of Love.

Amid the various protest movements on SF State’s campus in the 1960s, there was also the kind of activism that took the form of service.

The Summer of Love was bringing in teenagers from all over the country to San Francisco. Meanwhile, SF State students were going into city schools to tutor at-risk kids. Students hoped to persuade them to stay away from the scene in the Haight-Ashbury and Golden Gate Park, SF State Special Collections Librarian Meredith Eliassen said.

“While everybody was partying in the Haight, our students were coming together to network, to do activism and to do work in the community,” she said.

Community service became especially important in San Francisco during the Summer of Love because of the influx of tens of thousands of young people into the city, SF State Humanities Lecturer Peter Richardson said. People were getting sick, going hungry or couldn’t find proper housing, he said.

“I think part of it was that the city wasn’t supporting the Summer of Love. They kind of resisted it. A lot of city officials were saying, ‘don’t come.’ And people in the Haight-Ashbury realized that they had to do it themselves,” Richardson said.

There was Huckleberry House, which still shelters runaways, and the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic, which offered drug treatment and psychiatric care. The Diggers, a group of street actors and radical activists, had a free food service every day at 4 p.m. and also ran a free store. There was also the Haight-Ashbury Switchboard, which relayed information for people who wanted to find a place to crash.

At SF State a few years earlier, the Associated Students had established a community-based tutorial program for low-income children. Hundreds volunteered at a dozen locations around the city.

In 1965, the Experimental College was founded, offering free courses taught by professors, students and community members. The college’s focus on individualized instruction echoed the philosophy of the University’s founding president, Frederic Burk.

The college was a driving force for social service on campus, and out of it came the Community Services Institute, which developed work-study programs and allowed students to earn academic credit for volunteer work.

These were important developments for the University, and they reflected the self-sufficient and community-centered spirit of the time, said Jason Ferreira, an associate professor in the College of Ethnic Studies.

According to Eliassen’s 2007 history of the University, student Roger Alvarado also established a tutorial program in the Mission District, and members of the Black Students Union tutored black kids elsewhere in the city. Some of those then enrolled in SF State after finishing high school and were participants in the 1968-1969 student strike, which Alvarado and the Black Students Union organized.

SF State students also advised fellow students on how to best to deal with the Selective Service, the federal agency that administers the military draft. Draft Help offered information on how to get student deferments and how to become a conscientious objector, but also on how to volunteer for the Army.