Presidio relics give professor clues to soldiers’ past

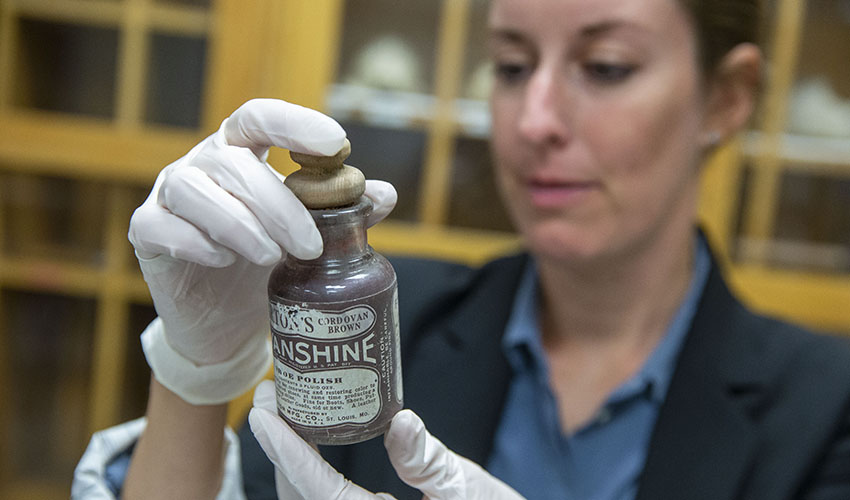

SF State Professor of Anthropology Meredith Reifschneider examines items from the old army barracks at the Presidio.

Artifacts from men’s army barracks tell story of health care in the 1890s to 1950s

Empty whiskey bottles, crumpled cigarette packs, dental floss, packaging from an old Colgate toothpaste package — it might sound like trash, but to San Francisco State University Assistant Professor of Anthropology Meredith Reifschneider it’s a treasure trove. Reifschneider is sifting through such items — found in enlisted men’s barracks at the Presidio, now a national park in San Francisco, that date back to the 1890s through the 1950s — for her current research project. With each discarded, once-worthless item she’s creating a clearer picture of the everyday health care practices of people of the past.

Reifschneider’s interest is in medical anthropology, specifically how health care and medical practice developed in the U.S. in the last 100 to 150 years. She heard rumors the park pulled items from the men’s barracks and thought they could be valuable to her research. She contacted the Presidio Trust, the organization that now oversees the artifacts after the Army left the base in 1994, and it agreed to loan out the items.

Workers discovered the artifacts in the rafters during a planned renovation of the barracks in 2009. Men were hiding things they didn’t want found by supervisory personnel, Reifschneider says. That explains the large number of alcohol bottles and cigarette packages — stuff soldiers shouldn’t have had in their quarters, she adds. But there were also everyday items like dental floss, chewing gum packages and toothpaste. Because public health became a national priority during the 1890s, there were pamphlets about dental hygiene, foot care and hair care, as well.

The items bookend the Progressive Era, a time of great political and social reform, Reifschneider says. Women’s suffrage, prohibition, vaccinations and housing reform were all hot topics, and the objects show how such cultural debates and policy shifts trickle down to daily life.

“This stuff might be considered trash, but our trash says a lot about who we are and how we lived,” Reifschneider added.

The items filled 75 boxes, 10 of which have already been catalogued by Reifschneider and a handful of students. The next step is to create historical biographies of each object, she says. That means studying packaging from a rumpled box of Colgate toothpaste, for example, tracing the manufacturer’s history and finding out how accessible the product was at the time.

“We’re learning how these objects were used, especially within a military context, and trying to tease out what daily life was like within the U.S. Army, which we don’t have a lot of historical records about,” Reifschneider added.

The artifacts capture this middle ground the soldiers inhabited, Abell-Selby says. “In the Army, you don’t have a lot of autonomy or free will, but this barrack was a place where people could have free will,” she said. “It was their home within the institution.”

San Francisco State senior Emma Abell-Selby has been assisting Reifschneider with the project since last year and has her own research agenda. At a conference this spring she’ll present research in the form of a poster about how soldiers complied with and deviated from the Army’s rules. “They were smoking and drinking, but since they were within the institution they had to make sure their health was intact,” she said. “They had to floss, use toothpaste and make sure their teeth didn’t rot out.”

And the items reflect that. They’re a mixture of banal everyday products, like shampoo and paper with doodles, and items specific to the military, like targets and rope. “What’s really poignant is that these are people who are both unfamiliar and familiar,” Reifschneider said. “You can envision the life of these men, who are probably incredibly bored just sitting around the barracks at night. They are doodling, drawing, drinking and participating in things we associate with civilian life.”

Reifschneider and a few students will be sharing more information about the project at the Presidio’s International Archaeology Day on Oct. 26. She says she’s also looking for volunteers, particularly ones with a military background, and student assistants to help her continue her research.