New quarter honors alumna elected first female Cherokee Nation chief

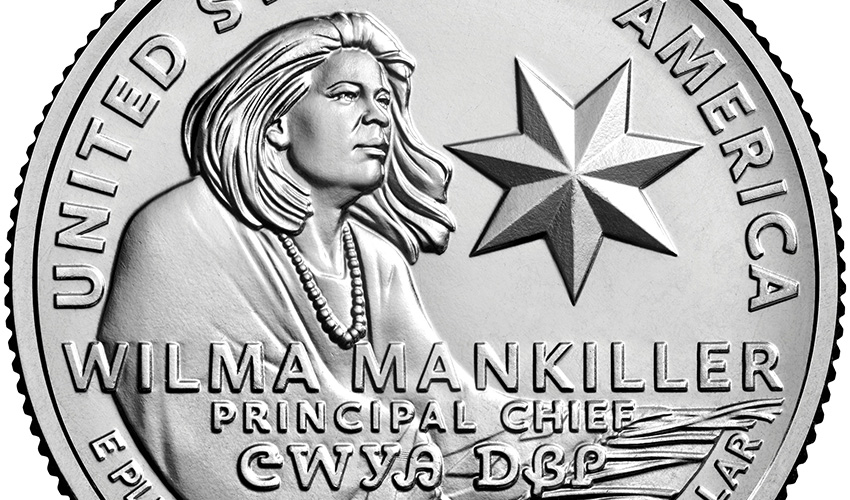

The Wilma Mankiller Quarter is the third coin in the American Women Quarters Program. Wilma Mankiller was the first woman elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and an activist for Native American and women’s rights.

Activist Wilma Mankiller attended SF State years before becoming the leader of her tribe

The latest United States Mint quarter recognizing trailblazing U.S. women features alumna and 1995 San Francisco State University Alumni Hall of Fame inductee Wilma Mankiller — the first woman ever elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. The American Women Quarters Program celebrates the accomplishments and contributions of women who have transformed U.S. history. This four-year program, ending in 2025, has already featured luminaries like writer Maya Angelou, astronaut Sally Ride and Chinese American film star Anna May Wong.

The new coin design shows the late Mankiller with a “resolute gaze to the future,” the U.S. Mint said in announcing the design. She is wrapped in a traditional shawl with the Cherokee Nation seven-pointed star, and “Cherokee Nation” is written in Cherokee syllabary. Mankiller’s legacy is alive and well and continues to influence today’s tribal leaders, said Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. at a recent event celebrating her legacy and the new quarter.

Wilma Mankiller

“Even years after her passing, chief Mankiller is still making an impact,” Hoskin said. “Right now as we speak the Cherokee people remain organized in their communities. … That spirit of ‘gadugi’ (which in the Cherokee language means working together) is alive and well because of chief Mankiller’s efforts to inspire our people to work together at the grassroots to build strong communities.”

Before she was a trailblazer, Mankiller, whose name signifies a traditional Cherokee military rank, was born in 1945 on a 161-acre tract in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The family’s land was given to her grandfather by the U.S. government after he was driven from Cherokee tribal land in the Carolinas. Mankiller, one of 11 children, grew up in poverty without electricity, indoor-plumbing and telephone lines. When she was 10, her father moved the family to Hunters Point, San Francisco as part of a Bureau of Indian Affairs program to assimilate Native Americans through urbanization. Her father also wanted a better life for her family, but Mankiller had trouble adjusting and called the move her own “Trail of Tears” in a 1993 interview with The New York Times.

As the 1960s unfolded and the nation’s youth gravitated toward progressive ideals and activism, Mankiller dove right in, too. The decade transformed her from a complacent housewife to a budding activist fighting for Native self-determination. In 1969, Mankiller was emboldened by the actions of San Francisco State student Richard Oakes and the dozens of other Native American activists who took Alcatraz and claimed it for Indians of All Tribes. During the group’s 19-month occupation of the island, Mankiller visited several times and raised money for their cause.

“I had felt there was something wrong with me because I wasn’t happy being a traditional housewife,” she said to The New York Times. “What Alcatraz did for me was, it enabled me to see people who felt like I did but could articulate it much better. We can do something about the fact that treaties are no longer recognized, that there needs to be better education and health care.”

At odds with her old life, she pursued college, first at Skyline College and later at SF State. At the same time she also spent time at the Indian Center in San Francisco helping with fundraising and organizational efforts. She later became acting director of East Oakland’s Native American Youth Center.

Mankiller later reflected on her time at SF State, when campus was alive with debates about the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, Black, Brown and Red power and the women’s movement. “I remember a wonderfully lucid debate about whether a Ku Klux Klan member should be allowed to speak on campus. That debate caused me to think through important questions about free speech which served me well when, as an elected leader of the Cherokee Nation, I was faced with dissenting voices. I remained a strong advocate of free expression and free speech in large part due to my experiences at San Francisco State,” she said.

After divorcing her husband, her life came full circle. She returned home to Oklahoma in 1976 with her two daughters and began working for the Cherokee Nation. After serving as deputy principal chief from 1983 to 1985, Mankiller served as principal chief between 1985 and 1995. Under her leadership, she revitalized the Cherokee Nation by tripling tribal enrollment, doubling employment, improving tribal health care and developing new housing and programs for children.

In 1990, she signed a historic self-determination agreement in which the Bureau of Indian Affairs gave the tribe authority over millions of dollars in federal funding. In 1998, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom under Bill Clinton. She retired from office in 1995 but fought for the advancement of Indigenous people until her death from pancreatic cancer in 2010.

To order a Wilma Mankiller U.S. quarter, visit the U.S. Mint’s online catalogue.