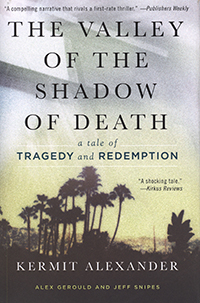

Book illuminates true-crime story of tragedy and redemption

Assistant Professors of Criminal Justice Studies Alex Gerould and Jeff Snipes spent more than four years researching the 1984 Alexander murders for their new book, "The Valley of the Shadow of Death."

Two women and two children are murdered in their South Central Los Angeles home. The crime is brutal, shocking and seemingly random. There are no leads. A family is shattered. A son, searching for answers, is driven to depression and desperation.

The tragic details spill onto the page as in a murder-mystery novel, but the story is heartbreakingly true. A new book by San Francisco State University Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Studies Alex Gerould and Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Studies Jeff Snipes and former NFL player Kermit Alexander, "The Valley of the Shadow of Death," explores the details surrounding the tragic murders and provides an illuminating look at the African American experience over the last 70-plus years.

"It deals with Southern life in the 1940s and '50s, with Jim Crow and with the Great Migration out west. It deals with L.A. and its promises. It deals with the disappointments, the street gangs, the criminal justice system," Gerould said. "It's really an encapsulation of both the intimate and the grand, and that's what we wanted."

The intimate is the life of Alexander, whose mother, sister and two young nephews were killed on Aug. 31, 1984 and with whom Gerould and Snipes share co-authorship of the book. Written in Alexander's voice, "The Valley of the Shadow of Death" details his childhood in Louisiana, his family's move to California, his NFL career, his descent into the L.A. underworld following the murders in a desperate search for answers and, ultimately, his redemption years later.

The grand is how Alexander's story fits into the broader context of life as an African American since the early 20th century. Like so many others, Alexander's father moved his family from the South to Los Angeles in the hope of escaping Jim Crow discrimination and finding new opportunities. But they found, as so many others had, the relief was only temporary.

"Kermit has expressed this to me so much, that the fear and the injustice that they left in the South was relived in a new incarnation in South Central L.A. with the rise of street gangs," Gerould said. "Many of the people who fled the white supremacists and the terror in the South were now terrorized by their own race in their own neighborhoods."

The result of four years of exhaustive research and interviews, the book had its genesis during a visit by Gerould and Snipes' criminal justice studies class to San Quentin state prison. During the visit, Gerould overheard a guard say that the most dangerous man on death row was Tiequon Cox -- a central figure in the Alexander murders. That sparked his interest in writing a book about the case, and he asked Snipes to work with him on the project. They soon discovered some 20,000 pages of court documents that offered not only details of the trials but also revelations about what life was like in gang-ridden Los Angeles during the 1980s.

"One of the things that surprised me the most was just how much information we were able to come up with on such an old case," Snipes said. "Another was the ability to interview most of the people who were actively involved in this case and how willing they were to talk about it."

Gerould and Snipes reached out to Alexander, who eventually agreed to talk and invited several relatives to meet with the authors at Alexander's home in Riverside.

"It was the first time the family had really met and talked about the case since it had happened, and we were there, which was pretty emotional," Gerould said.

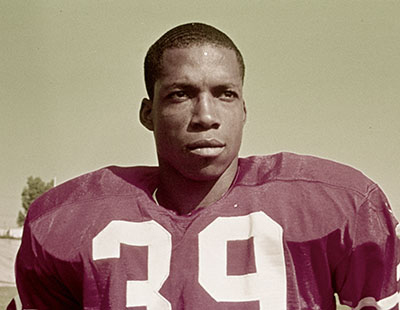

Kermit Alexander, a former NFL and San Francisco 49er player, worked extensively with Gerould and Snipes to provide intimate details about the devastation he faced following the murder of four family members. Photo: Associated Press

Initial plans were for the book to be written in the third person, but all parties eventually agreed the story would be much more powerful if told from Alexander's perspective. Hours-long interviews with Alexander and his relatives provided the intimate details Gerould and Snipes needed to tell the personal side of the case: the shock and devastation of the first few hours and days following the killings, the divisions that occurred as the case dragged on with no answers and, ultimately, healing for both the family and for Alexander.

In addition to speaking with the Alexander family, Gerould and Snipes wanted to better understand the African American experience and the realities of life in South Central L.A. They visited death row at San Quentin and Alexander's hometown in Louisiana. They drove the route the killers took. They spoke with gang cops and active gang members to learn how countless young men, often from broken homes, are driven to a life of violence in exchange for the "protection" gangs offer.

"You see how violent and brutal the effect of gang violence is on the victims, and at the same time you see how the gang in a very unfortunate way makes sense to the kids who join it," Gerould said. "I understood in a way I hadn't before why all the stuff you read in the theory books actually takes place."

During the writing process, Gerould and Snipes' families have become close with the Alexanders, and Snipes says he hopes Kermit Alexander's story of redemption helps readers understand how, with patience and perseverance, good can ultimately come out of tragedy.

"This book changed Kermit's life, and so in that sense it also changed our lives," Snipes said. "He had this stuff bottled up, and being able to finally get it all out there has gotten him to this point of closure, and he now feels at peace. We're so happy for him and so glad to have been a part of this."